Mikel Arteta: ‘I don’t ask for people to like me or love me. It is who I am’

Mikel Arteta is extremely intense. That much becomes pretty clear, pretty quickly during the early episodes of All or Nothing: Arsenal – Amazon’s fly‑on‑the-wall documentary of the club’s 2021‑22 season. His team talks are life and death: opponents are there to be killed, expletives screeched. “Whatever happens I don’t want one fucking player complaining, one fucking player walking,” he demands from the Emirates Stadium changing room at half‑time, before sending the team back out to face Chelsea.

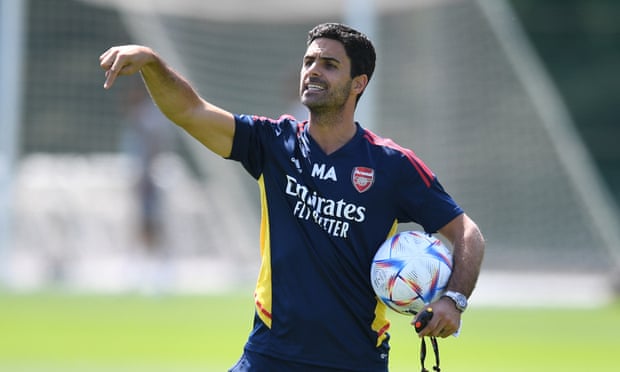

His intensity doesn’t let up as I sit opposite him, on a picnic bench outside Arsenal’s London Colney training centre, before the documentary’s release. “It’s who I am,” Arteta says, as he dispatches my questions with a ruthless efficiency and the unfaltering stare of a hawk studying its prey.

“The passion that I feel for this game, for this club, is what drives that emotion and that level of participation and that desire and hunger to be the best and improve at all times.”

The 40-year-old Arteta is the linchpin of Amazon’s latest reality‑documentary series. Others drift in and out with single‑episode arcs but his narrative presents the clearest through-line: can the league’s youngest manager lead its youngest team from rock bottom to improbable heights?

The answer: sort of.

After losing the first three games, Arsenal finished fifth, in the Europa League places, higher than the eighth of the previous two seasons, but they did so after giving up a commanding position for the much-coveted fourth Champions League place to Tottenham. Most Arsenal fans (of which I am one) would agree the season represented steady progress on and off the pitch, if not a resounding triumph. As for the manager, he silenced many of his critics.

“I don’t ask for people to like me or love me,” he says. “It is who I am. That’s their choice. And my choice is always … to try to be myself and be the person with the values that I have been raised with.”

Self-image is of little importance. “It doesn’t [concern me] but it concerns my loved ones and obviously everybody likes to be liked. But what I guarantee you are going to see is who I am and not only me, about who we are as a club, which is the most important thing, much more important than me, and that perception, hopefully, is positive. That worries me much more than my personal one.”

At times our conversation feels like an extension of the series: a club-managed, carefully curated peek behind the curtain. He is affable and courteous, but guarded. Shortly before we are due to meet the promised interview time is significantly cut down; not even my assurances that I’m an Arsenal season-ticket holder can persuade him to stay and open up. Perhaps it is out of shyness; perhaps a general distrust of the media (he regularly highlights media hostility toward him throughout the series).

Arteta’s trepidation is probably understandable, given the intensity of the criticism he received last season. Arsenal’s shocking start to it is well documented: deservedly beaten by Brentford, Chelsea and Manchester City; zero points and zero goals; bottom of the league. Discontent culminated in a number fans confronting the manager in his car after the Chelsea match.

If Arteta holds any lingering resentment towards those who turned on him so vociferously, he is not showing it. “Well, they express their feelings [when] we are losing football matches and we are here to win and we should never forget that. We can have the best intention but you have to win football matches. And when you don’t as a manager, you get sacked. It’s as simple and as clear as that.”

It is an evasive answer but he is at least more direct about fans such as me who had their faith in him and the club restored over the course of the season. “I’m so grateful that now they are happy that we are continuing this journey together, because without our supporters it doesn’t make any sense what we do.

“One of our biggest responsibilities – and [it’s a] beautiful thing – is to make people happy and enjoy certain moments in their lives. And we are responsible for that, and it is a big pressure, but at the same time is an incredible power to have.”

After the first three defeats Arteta chose his pre-match talk in the next game against Norwich to share a story from his childhood. He was born with a heart condition that stopped his heart getting the right supply of clean blood. At two years old he had surgery, becoming one of the first in Spain to undergo such an operation. The doctors ruled out sports. But by the time he was three he was in love with football; he still remembers his first black and white ball and his first football shirt (Barcelona).

“I was much more aware [of the heart condition] when I was developing and growing, because there were some issues and there were some restrictions, but I was probably not conscious about that [potential repercussions]. My parents were. They were really brave, because they push and push and push and [said]: ‘We’re going to try to get the best doctor to give us advice.’ They were really honest, but at the same time brave, to allow me to do certain things.”

His mum always worried about him playing. “My mum never wanted to watch me play because in the back of her mind that issue was always there, that when I push my heart to the limit, what is going to happen?”

And his dad? “My dad was a bit stronger and I think realised: ‘I’m not going to stop him whether he’s a professional footballer or he plays with the amateurs. [No matter how] competitive it is, he’s going to play the same way.’”

Arteta was, he says, a very active child who played a lot of tennis, as well as football. He struggled to sit still. “It was difficult to keep me seated on that table. But I was pretty responsible. So when I knew that I had to do something. I always did it.”

Judging by Arteta’s reputation as a manager and a player it is easy to imagine him as a well-drilled, highly disciplined child. “My father in that sense was really, really disciplined with me. The threat was simple and very effective: if you don’t do it, you don’t play football. So it was no choice for me.”

Does he channel his father in his management of his players? “The way you’ve been raised and educated is a huge part of who you are as a person – as a father as well, to try to get those values across to your kids as well. So this is what I try to do.”

In nearly three years as a manager Arteta has established his reputation as a staunch disciplinarian with his “non‑negotiables” of respect, commitment, passion, a studious tactician and an effective coach. Granit Xhaka labels him a freak (“but in a positive way”), such is his attentiveness to the small details. He also seems to enjoy quirky team talks.

Before the Leicester match at the King Power stadium, he has the squad standing in a circle, rubbing their hands together as they visualise their success in the match, before grabbing each other’s hands and creating a bubble of energy. It’s a lot less cringe-worthy than it sounds and Arteta’s impassioned delivery helps him skirt any comparisons to David Brent (and in fairness the 45 minutes that followed was some of Arsenal’s best of the season).

Is he studying management techniques in his spare time? “A lot. I like to read about other industries, a lot of sports. I have a lot of connections with other sports that are super rich in terms of how they manage the culture, how they manage different situations, how they apply the methods into the style of play that they want.

“A lot of my education, it doesn’t stop here. Languages – if I could learn German, I will do it tomorrow, if I could. I think wWhen I have time and when I’m in the car I’m always spending my time doing things like that.”

Arteta rejects the idea he is a natural leader – “The role gives you the possibility to become a leader but the players decide who the leader is and they have to feel it” – and when asked why players buy into him with such fervour, he deflects to the collective.

“We have the right people here to try to convince them they are in the best club in the world, trying to do the right things, things that are beneficial for them, that they’re going to feel protected if they fail and that they’re going to be trusted to do what we asked them to do. You cannot do that by yourself.”

As for the hardest aspect of management: “Probably that line between how personal it gets and how professional it gets and when … you have to make a decision based on the professional.” He doesn’t elaborate on specifics, but I’m not sure he needs to.

He says he has lost sleep over the job, breaking into a rare smile, though he quickly adds that such insomnia is infrequent. “I think I’m quite good at getting to sleep. One thing really important for me is to make sure that what is happening tomorrow is under control. And the things that I have to do tomorrow, they are already on the way to getting done. If I don’t have that, then I find it really, really difficult.”

For Arteta one of the biggest challenges of the job is not bringing his work home with him, made all the harder with his three boys – aged 13, 10 and seven – having caught the football bug. “They love football and very naturally they will ask me what happened or why didn’t he play?” And ask for updates on the summer’s transfer business? “Yes, the whole summer,” he says, with an air of exhaustion.

Do they at least have a set of non-negotiables similar to your players? “They do have, especially with their mum, because she’s the one that spends long hours and [takes] the responsibility with them. So mum is the one that they really need to look after … and I’m really lucky because they are pretty amazing kids.”

Watching Arteta in the documentary, it’s impossible not to think of Arteta’s old boss Arsène Wenger and his own obsessive commitment to the game.

When Wenger released his memoir last November, he spoke about his regret at not taking care of his family in the way he should have. Football always came first. Is Arteta worried about making the same mistake? “People talk about the balance between family and football or your job and at the moment there is no balance. What I’m getting better at is giving them more quality time when I’m there.

“I was conscious of [the time commitments] on day one. I don’t know if I was 100% conscious of what it was going to take but I made that decision and I’m fully aware of that. I’m so happy to be where I am.”

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

-

How to get a free jersey

- How to get Pcs free jerseys Feedback Customer Reviews About Us Contact Us News FAQ

-

User Center

- Forget Password My Orders Tracking Order My Account Register

-

Payment & Shipping

- Customs & Taxes Locations We Ship To Shipping Methods Payment Methods

-

Company Policies

- Return Policy Privacy Policy Terms of Use Infringement Policy