The fight is eternal, and there are always new enemies to trounce and new ways in which to trounce them. As Ronaldo prepares for his second debut against Newcastle United on Saturday, the terms of success remain unclear. The merits of his transfer will continue to generate debate until United end their wait for a big trophy. But ultimately, you can’t argue with the numbers.

The Ronaldo phenomenon: how one player became a tyranny of numbers

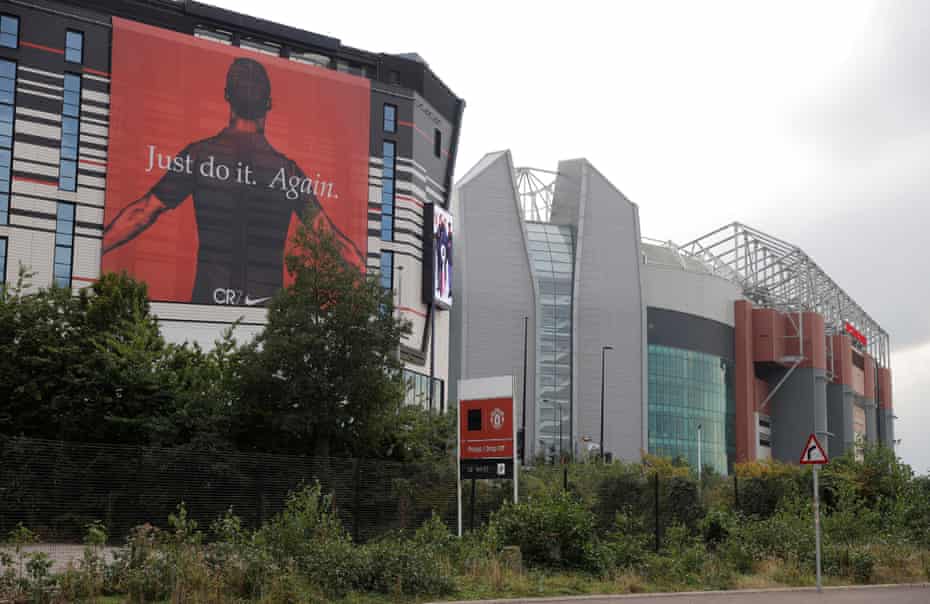

In the aftermath of Cristiano Ronaldo’s shock return to Manchester United last week, there was a good deal of feverish speculation about whether he would reclaim the famous No 7 shirt once worn by United legends such as George Best, Bryan Robson and Eric Cantona, and which now forms a central part of his “CR7” personal brand.

But there was more than iconography and nostalgia involved here. The No 7 shirt already had an occupant: striker Edinson Cavani, and under Premier League rules Cavani was required to retain it for the season. Yet when you are as famous as Ronaldo, it turns out that there is an extent to which you can make up your own rules. When you see something you want, you don’t get too hung up on niceties and boundaries. You take it, as firmly and assuredly as if it had been yours all along.

There was a kind of breathtaking ruthlessness to the way Ronaldo simply annexed the United No 7 shirt in a matter of hours: the necessary hurdles cleared, the necessary rules relaxed, the necessary arrangements made. Daniel James was sold to Leeds. Cavani was persuaded to relinquish the No 7 jersey in favour of James’s old No 21, the shirt once worn by United legends Henning Berg, Diego Forlán and Dong Fangzhuo.

Still, with the possible exception of Cavani, everyone got what they wanted. In its first full day on sale, the “Ronaldo 7” replica kit broke United’s daily record for shirt sales. In press briefings, the club gushed about the social media impact of the transfer announcement: the 13 million likes on their Instagram post, the fact that Ronaldo’s move to United had beaten Lionel Messi’s move to Paris Saint-Germain by 700,000 Twitter mentions.

This is in keeping with the nature of the Ronaldo phenomenon at large: a tyranny of numbers, a bewildering maelstrom of records and statistics that the player’s many fans all over the world like to blazon and trumpet as empirical evidence of their man’s supremacy. The numbers aren’t the adjunct to a wider point: they are the point. It is a curious sort of greatness, the sort that is not really meant to be appreciated or discussed, but rather something that is aggressively forced upon you, wielded like a blunt weapon.

This is not to say Ronaldo doesn’t inspire feelings. It’s just that they’re not the sort of feelings one normally associates with collective success in a team ball sport.

Delve into the howling wildernesses of the internet, on sites such as Reddit and 4chan and men’s fitness forums, and what Ronaldo embodies above all is something larger than simply goals and medals. To a certain cross-section of disaffected young males from which he seems to draw the core of his fanbase, he represents a sort of ultimate masculinity: vindication, vengeance, pride, indestructibility, physical dominance, the satisfaction of crushing your enemies underfoot. Ronaldo wins, and so by extension everyone else – including the “manlet” Messi – loses.

To an extent this is simply the brazen, warlike nature of online idolatry. But more than perhaps any footballer who has ever lived, Ronaldo has also cultivated this brand of individualistic devotion around himself. Watch one of Messi’s many endorsement adverts and almost invariably he is entering some sort of social setting. Messi turns up on a plane and starts kicking a ball around. Messi turns up at a petrol station and starts kicking a can of soft drink around. Messi turns up at your flat party bearing crisps.Almost without exception, Ronaldo adverts feature him and him only. Ronaldo lit against a dark background, holding a bottle of shampoo. Ronaldo alone in his empty mansion, surrounded by prickly plants and gold ornaments. An oiled and grimacing Ronaldo doing sit-ups. If anyone else is present it is invariably a woman, sultry and mute, moved to the very brink of ecstasy by Ronaldo’s mere presence, his smell, his ability to perform keepy-uppies with a CGI moon.

There is a distinct, curiously insular world view being presented in these adverts: one that goes beyond a simple narcissism and reimagines the self as a sort of live project, a machine being continually honed and improved in the name of conquest. There’s no greater meaning in the world out there, beyond the meaning you will impose upon it. The fight is eternal, and only one person can win it, so you’ll need a regime. Do the sit-ups. Take the online degree. Use the pearlised mica-white anti-dandruff shampoo. Win a woman.

Of course, Ronaldo the person is a much more complex and conflicted individual than popular representations of him would have you believe. The manner in which he hauled himself out of his impoverished upbringing in Madeira through clear-eyed ambition and a superhuman work ethic continues to provide a source of genuine inspiration to many. And yet there are times when it is not entirely clear where Ronaldo the man ends and Ronaldo the cult begins.

In 2018, Ronaldo was publicly accused of rape by Kathryn Mayorga, a former teacher who claimed in Der Spiegel that Ronaldo had forced himself upon her in a Las Vegas hotel room in 2009. (In 2019 police concluded that criminal charges could not be brought as the accusation could not “be proven beyond reasonable doubt”.)

Ronaldo has always denied raping Mayorga, describing the allegations as “fake news”. Meanwhile, those around him immediately mobilised a counter-strategy. In the weeks after the Der Spiegel investigation was published, Ronaldo’s mother and sister posted a picture of Ronaldo in a Superman cape, and urged his fans to do the same. Ronaldo’s lawyers described the accusations as “outrageous”, an attempt “to destroy a reputation built thanks to hard work, athletic ability and behavioural correction”. To this day Mayorga continues to be subjected to vicious, misogynistic personal attacks on social media.

Of course, Ronaldo can hardly be expected to bear responsibility for the thousands of creepy fanboys posting abuse in his name. But for whatever reason, his feats on the football pitch have attracted a certain strand of angry young male towards him, the sort motivated less by his peerless penalty-box movement or immaculate technical ability than by what they feel he stands against.

Or as his friend Piers Morgan put it in a recent Mail on Sunday column: “In a woke-ravaged world that increasingly seems to celebrate failure and weakness more than success and in which quitting in sport is now inexplicably seen as brave and heroic, Ronaldo is a refreshingly unashamed advocate of winning and resilience.”

And so while Messi regretfully leaves Barcelona in a flood of tears and turns up at Paris almost despite himself, Ronaldo seemingly returns to United in triumph, the master of his own destiny, again bending the gravity of football to his will. This is why the speed and manner of his arrival – and the gushing, reverential coverage that followed – felt like its own statement of power, cucking Messi, Manchester City and Cavani in a single awesome swoop. Naturally, there will be haters and doubters arguing that Ronaldo doesn’t press, that his best years are behind him, that United still don’t have a midfield. But how many sit-ups have they ever done?

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

-

How to get a free jersey

- How to get Pcs free jerseys Feedback Customer Reviews About Us Contact Us News FAQ

-

User Center

- Forget Password My Orders Tracking Order My Account Register

-

Payment & Shipping

- Customs & Taxes Locations We Ship To Shipping Methods Payment Methods

-

Company Policies

- Return Policy Privacy Policy Terms of Use Infringement Policy